Research in our lab

Many of the world’s staple crops are vulnerable to the emergence of new pathogens. Genetic homogeneity of crop plants and fungicide applications drive rapid adaptive evolution in pathogen populations. Our group investigates the genetic architecture of adaptive traits and retraces genome evolution in major crop pathogens.

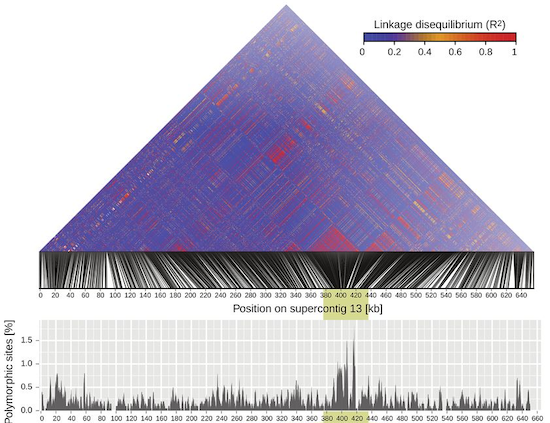

Our main model is a worldwide pathogen of wheat called Zymoseptoria tritici, which causes the most economically damaging foliar disease in Europe. The pathogen has overcome most resistance of the host and all currently available fungicides. Genomes of this pathogen show an extraordinary level of sequence and chromosomal polymorphism unlike many other pathogens. One of our major aims is to understand how major adaptive traits evolved. For this, we perform genome-wide association studies (GWAS) to map phenotypic traits to individual loci in the genome. We focus in particular on different components of pathogenicity but are also interested in stress tolerance against fungicides, temperature and conditions experienced during infection (low pH, oxidative stress). To understand the process of adaptive evolution, we analyse major effect loci for signatures of selection and sequence rearrangements.

We are fascinated by the rapid dynamics of transposable elements (TE) in genomes. We believe that the compact yet dynamic genomes of fungal plant pathogens are quite unique models to address fundamental questions about the genome biology of TEs. We focus on what facilitates and constrains TE evolution in genomes by analyzing the shortest possible time scales (i.e. within species, populations or pedigrees). We investigate some highly active TEs that simultaneously made contributions to recent adaptation, the instability of chromosomes and the expansion of genomes. We also use large-scale screens of trait variation among individuals to associate TE dynamics to recent adaptation.

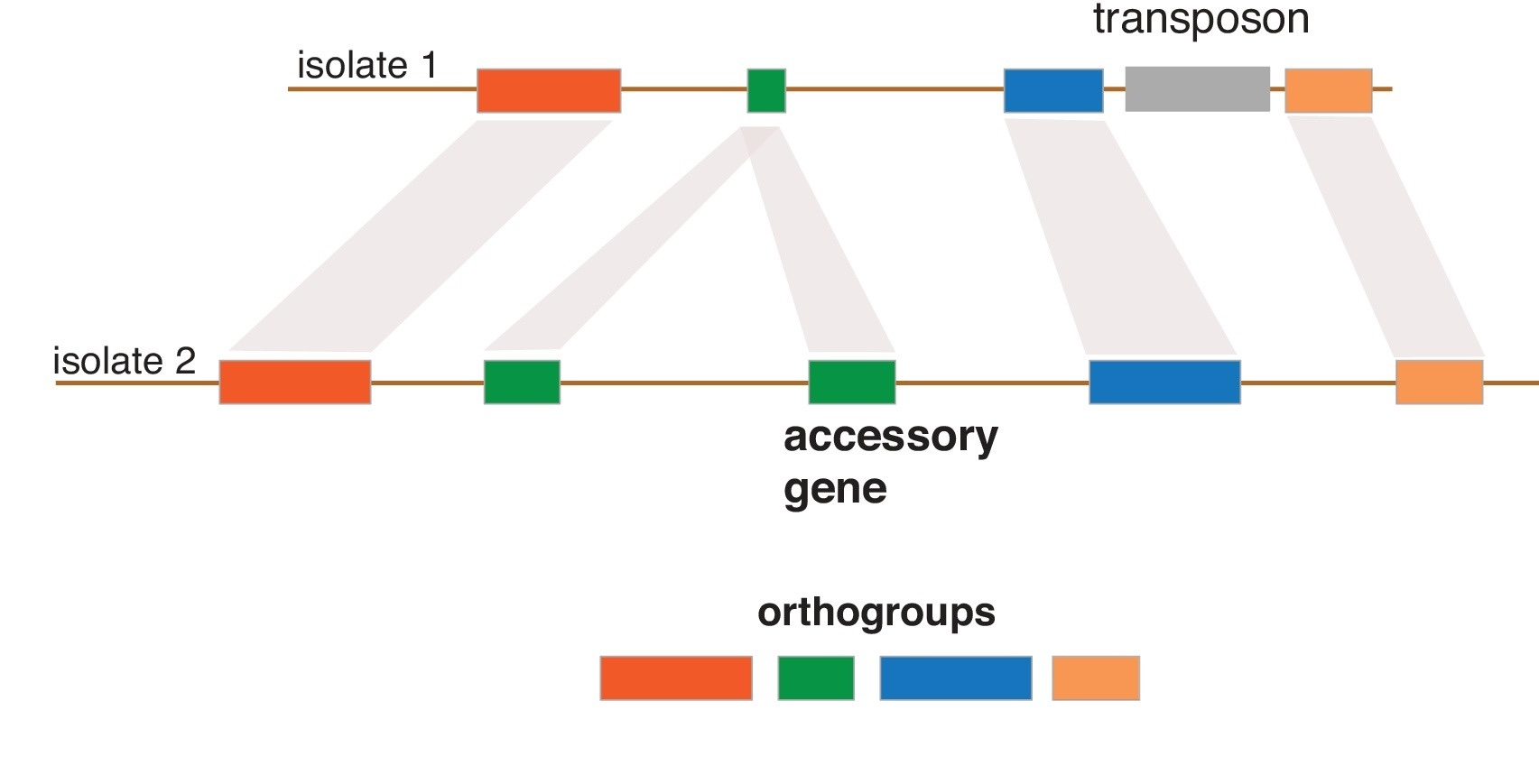

Our group is also interested in understanding the evolution of genome architecture. In particular, we want to retrace the emergence of novelty (e.g. new genes) and major structural rearrangements. For this, we assemble and analyse complete fungal genomes. We found that homologous Z. tritici chromosomes segregate significant structural rearrangements within populations and that such variation created key adaptations to overcome host resistance. The genome of Z. tritici also comprises a highly polymorphic complement of eight chromosomes that are not found in every member of the species. During meiosis, accessory chromosomes frequently undergo rearrangements, fusions and non-disjunction events. Our aims are to precisely identify the mechanisms responsible for the chromosomal abberrations and how chromosomal polymorphism is generated and maintained in populations.

Our group occasionally works on Cryptococcus and Malassezia fungi. These opportunistic pathogens of animals (including humans) are major threats to public health and provide fascinating models for the emergence of virulence. The most frequent infections are caused by C. neoformans (an estimated 625’000 deaths yearly). However, an ongoing outbreak in the North American Pacific Northwest and other continents is caused by the related species C. gattii which is able to cause disease in otherwise healthy individuals with a relatively high mortality rate. We use resequenced genomes of a large number of C. gattii strains to identify patterns of introgression and chromosomal rearrangements that shaped the genomic diversity in lineages. Malassezia fungi are implicated in a variety of skin diseases. We study the fungal diversity of Malassezia infections using genomic tools.

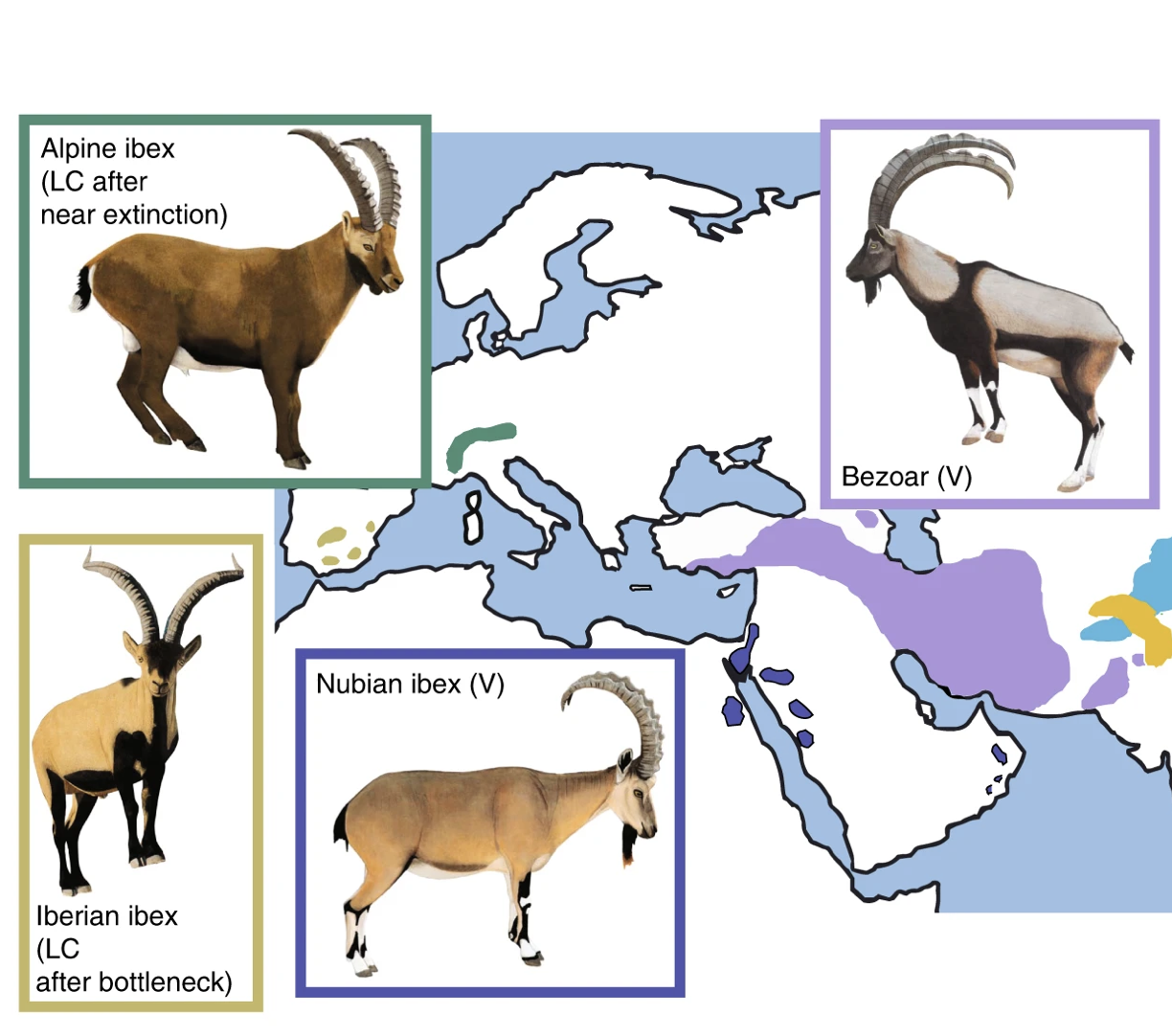

Our group collaborates on research projects on Alpine ibex, a flagship species for the successful restoration from near extinction. Alpine ibex suffered from a population bottleneck of a few hundred individuals caused by overhunting. The species was reestablished across the Alps and counts again around 40’000 individuals. We showed that Alpine ibex received genetic material from domestic goats through hybridization and introgression. A process that was likely favored by the population bottleneck. We are also interested in the consequences of population bottlenecks on the fate of deleterious mutations.